Of Kidnappings, Lions, and Crocodiles

The October 16 kidnapping of 17 expatriate missionaries in Haiti has generated a great deal of press attention.

Among the victims were 16 American citizens and one Canadian. The group is comprised of five men, seven women, and five children—including a toddler.

The gang that conducted the abduction, 400 Mawozo, is no stranger to kidnapping. They have reportedly kidnapped hundreds of victims over the past few years, most of whom are local citizens.

But they are also not shy about kidnapping foreigners or religious workers.

The previous April, nine Catholic workers were kidnapped. The hostages, two of whom were French citizens, included five priests and two nuns.

400 Mawozo released the Catholic group after payment of an undisclosed ransom.

It is important to recognize that not all kidnappings are the same. Most kidnappings involve parental custody disputes, human trafficking, sexual assault, and murder.

Only a small number of kidnappings are conducted for ransom.

There is hope that the current hostages may also be released unharmed despite 400 Mawozo’s threats to kill them unless the initial ransom demand of $1 million per hostage is met. (It is not unusual for kidnappers to make an unrealistic first demand while expecting to negotiate the final ransom payment down to a considerably lower number.)

Such financially motivated kidnappings are orchestrated by criminals that fall into two main categories with distinguishable methodologies. Each one requires different security measures to avoid them, and avoid becoming a victim.

Lions

One type of financially motivated kidnapper is the stalking criminal.

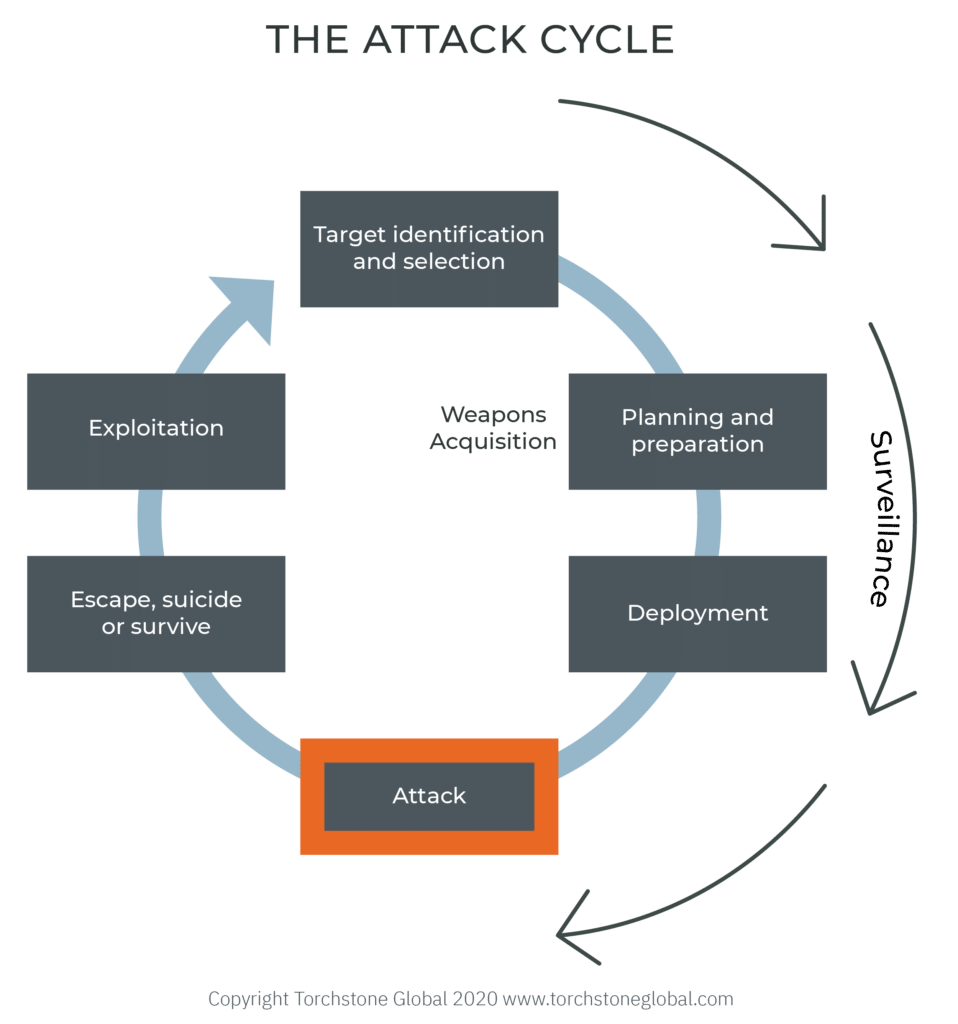

Like a lion stalking the savannah while searching for a suitable victim, these criminals conduct a slow, deliberate, attack cycle as they work to identify and select a specific target for their crime, and then carefully plan the abduction.

This criminal category includes high-value kidnap for ransom gangs, political kidnappers, and “tiger” kidnappers.

Tiger kidnappers are criminals who hold someone of value to their target hostage so they can compel them to do something. For example, holding the wife and child of a bank executive hostage to force the executive to open the bank vault.

Stalking criminals will often consider a number of potential victims during their target selection process and choose the one they believe presents them with the best chance of success.

During the identification, selection, and planning phase of the operation, these kidnappers will conduct extensive surveillance of their potential target as they attempt to identify patterns of behavior that present vulnerabilities.

This surveillance makes them vulnerable to detection by targets who are looking for surveillance.

Therefore, they tend to avoid targets who are surveillance-aware and who practice good situational awareness.

Since these criminals are looking for an easy mark, taking prudent personal security measures such as varying one’s routes and times, can often cause them to divert to a more predictable—and therefore easier to target—victim.

In some environments, the very presence of armed security will also deter such criminals. For example, we are unaware of any kidnappings for ransom in the United States in which the victim had an executive protection detail.

But in more violent environments, the very presence of security itself is no guarantee of safety.

If the criminals are permitted to conduct surveillance of the victim at will, and if they are able to quantify the security team and establish a solid pattern of activity that they can use to plan an attack, they may simply decide to bring enough firepower to overwhelm the security team.

It is not unusual in environments such as Nigeria or Mexico to see kidnappings where the victim’s security driver, and/or close protection officer, are shot dead during the abduction.

It is thus imperative that stalking criminals not be allowed to conduct unhindered surveillance.

Crocodiles

But 400 Mawozo are not stalking, lion-type criminals.

They did not conduct extensive surveillance on the missionaries they are currently holding hostage.

Instead, they are ambush predators, who, like a crocodile, lie in wait for a suitable and vulnerable target to pass their way and pounce.

Examples of ambush criminals include muggers, purse snatchers, some rapists, and express kidnappers. (Express kidnappers, as the name suggests, are kidnappers who only hold their hostage for a short time and for a relatively small ransom.)

However, when express kidnappers find they have grabbed a significant victim, they will often either transition into a long-term kidnapping for ransom, or else sell the victim to a gang that specializes in high-value kidnappings.

Ambush criminals operate on an attack cycle that is quite different from that used by a stalking criminal.

They spend more time selecting their attack site and then conduct an abbreviated target identification and selection phase as prospective targets pass by their ambush spot

When a suitable target presents itself, ambush criminals quickly launch their attack.

Such criminals can’t ordinarily be identified by surveillance detection efforts because they don’t follow the victim to the extent a stalking criminal does.

The amount of time they observe the victim before attacking is usually very limited. For the same reason, such criminals also cannot be deterred by the victim varying their times and routes. They don’t care what route the victim takes to get to their ambush site, just that they arrive and are vulnerable.

The best way to prevent an attack by an ambush criminal is obviously to avoid the ambush point.

One way to do this is to gather good granular intelligence about where, when, and how criminals operate in a specific area and then use that information to avoid potential ambush sites.

It was common knowledge among the expatriate community that the section of National Route 8 between Croix-des-Bouquets and La Source was dangerous to travel because of the presence of 400 Mawozo and other armed gangs.

In fact, reliable sources in Haiti report that the section of National Route 8 where the group was kidnapped has long been known to be controlled by 400 Mawozo, which frequently conducts roadblocks, kidnappings, carjackings, and cargo theft there.

It is not clear if the group that was kidnapped was aware of that information and chose to ignore it, or if they simply had not received the warning.

But there are a number of very good resources for granular security information about Port au Prince and Haiti that include US Embassy alerts, information shared through the local Overseas Security Advisory Council (OSAC) country council. A large and very active local WhatsApp group shares real-time security information among the expatriate community as well.

The information collected using such sources can be extremely valuable in guiding efforts to avoid ambush criminals.

It also helps provide high-level situational awareness about the general security environment.

Another way to avoid falling into an ambush is by practicing good situational awareness in order to recognize a trap in advance, whether it be a roadblock, backed-up traffic, or criminals exhibiting hostile demeanor or brandishing weapons.

Stopping well back from such a roadblock and rapidly leaving the site can, in many cases, help keep you from becoming prey.

Under most circumstances, I caution against attempting to run a roadblock manned by heavily armed criminals. It is better to be alive and kidnapped than it is to be dead. Especially so in a place where there is a history of hostages being released after a ransom has been paid.

Therefore, if you are caught in a trap, it is often prudent to surrender rather than attempt to run it.

However, the unfortunate truth is that kidnapping is a traumatic experience even when it is successfully resolved and the hostage is either released or rescued.

Kidnappings can also often be deadly when they are not successfully resolved.

No matter what type of kidnapper is involved—a lion or a crocodile—there are almost always indications of the pending threat. That means that nearly every kidnapping victim has either missed or ignored indications of the impending danger.

Awareness of the threat posed by kidnappers in a given environment, along with a proper level of situational awareness and practical, common-sense security measures can help ensure that signs of danger are not missed or ignored—and that the danger posed by kidnapping is avoided.

This article was originally written and published by Scott Stewart, Vice President of Intelligence at TorchStone Global and Protective Intelligence Honors Pioneer on October 29, 2021.