Protection Never Rests: The Deaths of the Iranian President and Foreign Minister

Hear from Fred Burton, Ontic’s Executive Director of Protective Intelligence and former special agent, on his experience with aircraft disaster investigations.

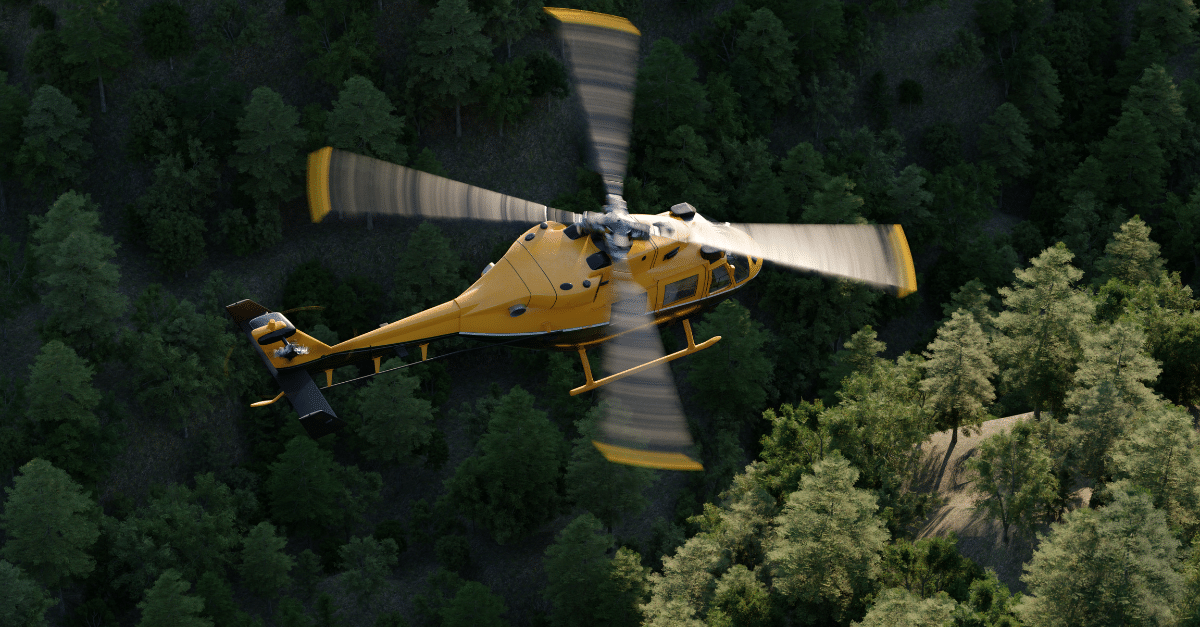

The May 19, 2024 crash of a Bell helicopter carrying Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi and Foreign Minister Amir Abdollahian appears to have been a tragic accident. When the crash occurred, Raisi was returning to Tehran in bad weather after traveling to Iran’s border with Azerbaijan to inaugurate a dam with Azerbaijan’s President Ilham Aliyev. The wreckage was found a day after the crash, hidden in a mountainous area in the Dizmar forest within Iran’s East Azerbaijan province.

This crash brings back bad memories of a horrific aircraft disaster I investigated in August 1988, the PAK-1 crash that killed the President of Pakistan, a U.S. Army Brigadier General, the U.S. Ambassador to Pakistan, and many others.

A Look Back at the Crash of PAK-1

On August 17, 1988, the Pakistani presidential aircraft, a C-130 code-named PAK-1, crashed near the central eastern Pakistani city of Bahawalpur. When I close my eyes, I can still see the smoking hole in the ground. Even when I arrived more than a day after the crash, it was a horrific scene and there were no survivors. Pakistani President Zia-ul-Haq, U.S. Ambassador to Pakistan Arnie Raphel, U.S. Army Brigadier General Herbert Wassom and several members of the Pakistani joint chiefs of staff, perished in the crash. At the time, Zia was a close ally of Washington and had spearheaded our covert war against the Soviets in Afghanistan.

Looking back on my career as an agent, the PAK-1 case may have been the most complex investigation I ever worked, which is saying something since life as a State Department special agent in the 1980s always seemed to be shades of gray. As a general rule, complex international cases were very hard to solve in those days — long before the internet or satellite imagery was widely available or amateur images were shared on social media. Even the simplest details took time to find and confirm, and nothing ever seemed to be black and white. But even in the counterterrorism business, some things turn out to be exactly what they appear. Following the physical evidence and keeping an open mind were an important starting point investigating any incident.

Within hours of the crash, I was traveling in an executive jet with another agent from our Counter-Terrorism Branch working on a U.S. Air Force Special Air Mission bound for the crash site. I had been on the job as a special agent for three years, but had already seen my share of mayhem and never ending terror attacks in that short time.

In Germany, we joined a U.S. Air Force Accident Mishap Team and boarded a huge C-5A Galaxy transport aircraft. Hours later, we landed at Chakala Air Force Base in Islamabad in the middle of the night. The on ground parts of the investigation began at the base, where we attended tense meetings with the Pakistani military and U.S. Embassy officials. President Zia had been one of the Pakistani Army’s top brass, but since the pilots were from the Air Force, tensions were very high and the blame game was in full swing. During that first stop, I also learned that the embassy’s Regional Security Officer (RSO) was slated to be on the flight, but in the 11th hour, the ambassador decided to make the trip instead.

We pushed on to the Bahawalpur crash site via a C-130 Hercules, an eerie experience since we were investigating the crash of another C-130 Hercules. We sped past dusty villages in Land Cruisers under heavy military guard with animals roaming through the streets, while the locals quickly got out of the way. We base camped in a military outpost a few miles from the crash site and over the next few days tried to put the puzzle pieces together as best we could. I’ve talked more about the details of investigation in my memoir Ghost: Confessions of a Counterterrorism Agent (Random House, 2008).

In retrospect, the crash site looked alot like rural West Texas. Dust devils swirled and the August heat was like a blast furnace. There were no houses or buildings anywhere in sight. The Pakistani military had set up a buffet of food about 25 yards from the black hole in the ground that was still smoldering days after the crash, but none of us could eat. At first glance, based on the outline of the impact zone, the wings of the Vietnam era aircraft appeared to have come down intact in the Punjab desert. The fire had burned nearly everything, though there were a few smaller pieces of the fuselage that had scattered at impact. Someone from the bottom of the crash pit handed me a badly burned black wallet.

The hours turned into days as we tracked down every detail. As the investigation progressed, we struggled to find first-hand accounts of the moments before the crash and the aftermath. Luckily, we stumbled upon a shepherd who said he had watched the aircraft go down. Motioning with his hands during the interview, the shepherd witness indicated the aircraft was moving up and down like it had been on a roller coaster prior to impact.

Sequence-wise, we were able to reconstruct several key points:

01

Three minutes into the flight, PAK-1 lost control.

02

For two minutes, the plane gyrated up and down.

03

No May Days or emergency alerts were given by the pilots, which became a key point.

04

Someone outside the flight deck shouted for the pilot just before PAK-1 crashed.

05

An unknown person keyed the radio before the plane went down, opening a sound link with air traffic control, but neither pilot spoke. It was as if the pilots were incapacitated and unable to speak.

Our investigation subsequently determined the crash was not caused by weather, catastrophic mechanical problems, and pilot error. Based on autopsy reports, we were also able to determine there had not been a fire on board prior to the crash.

But even though we ruled out the most common causes of aircraft disasters, we all knew C-130’s don’t just fall from the sky. Sabotage loomed large on our minds and the powers that be deemed that there would be only one official report, written by the Pakistanis.

Looking back, we did the best we could investigating PAK-1 and I’m confident I know what happened, as I wrote in Ghost. Curiously, a few weeks before the PAK-1 disaster, Eduard Shevardnadze, the Soviet Union’s Minister of Foreign Affairs, publicly stated that Pakistan would pay dearly for its support of the mujahideen in Afghanistan. A redacted and declassified Department of State telegram from October 1988 discussing the Pakistani accident report states, “The accident board attributed the crash to a probable criminal act or sabotage,” which was the conclusion of the Pakistani board tasked to determine the cause into how PAK-1 went down.

A New Era of Protection

The crash that killed Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi and Foreign Minister Amir Abdollahian was much different, and from an investigative standpoint, happened in a different era than PAK-1. All of the available public data makes the Raisi case seem very cut and dry, without the shades of gray we saw in 1988. Weather loomed large in this case, and even the most sophisticated helicopters can fall victim to dense fog and harsh terrain. In retrospect, traveling via an overland route or simply waiting out the poor weather would have been a far superior option, both to safeguard the protectee and to avoid disaster. In a time when VIPs are looking to get to their next meeting in a faraway place on time, finding ways to redirect the protectee to avoid looming and preventable tragedy may be one of the most difficult but important lessons to learn.