The Enemy of My Enemy is My Friend: Strengthening Insider Threat Resilience with Cyber-Physical Integration

A tactical approach to blending cyber and physical security intelligence operations

In part one of this two-part overview, I addressed many of the key themes and priorities required to mitigate insider risk properly. There has been a great deal of discourse relating to how an organization’s program can blend cyber and physical security intelligence operations to realize the outcome that we all hope to achieve. In this article, I want to dig in at a tactical level to show how this is achieved. It’s much more than having the right people, process, and technology — it’s also critical to recognize nuances of your business, including the vertical you are operating in, the company culture, and legal compliance requirements.

I often find that many organizations already have the bulk of the required information, data, and personnel to lay the groundwork for an insider risk program — they just need guidance or operational templates to start the process tactically. As important as the “how to” is the “why should we” and that is why you’ll require support from the entire C-Suite.

Lastly, it is essential as you consider your program development priorities to be able to point to nationally recognized standards. As a security leader, you can use these standards, compliance regulations, documented best practices, and benchmarking to help secure the proper approvals and create defensibility for your company’s action plan. Remove the onus from yourself having to prove why this is so important to implement and point to recognized methodologies. This will help educate key stakeholders and also help minimize the negative stigma that leadership may have about insider risk intelligence operations.

A strategic mindset

I spoke to Josh Massey, Department Manager at MITRE, about his methodologies and strategic mindset when implementing an insider risk program, and he had this to say:

“We either win together or lose together. At MITRE, we’ve structured our insider threat program to eliminate the artificial, functional turf wars of security silos in favor of an enterprise security risk management (ESRM) approach.”

— Josh Massey, Department Manager at MITRE

So, how do we start with the ESRM approach, and what standards do we use to lay the program’s foundation?

Several models and frameworks provide solid foundations for understanding ESRM concepts and how to apply them across security domains, enabling greater confidence from your C-suite, and then adapting to your vertical and organizational culture as needed.

For example, within the insider risk domain, the National Insider Threat Task Force (NITTF) has promulgated a maturity framework. Although this framework is meant to model a government agency’s program, numerous pieces can also be applied to the private sector. Some of the elements called out by the NITTF maturity framework are quite relevant to an ESRM mindset, including:

- Metrics: Employ metrics to determine progress in achieving program objectives and to identify areas requiring improvement.

- Risk management principles: Employ risk management principles tailored to address the evolving threat and mission needs.

- Cross-functional collaboration: Include stakeholders from a broad range of functional areas and others with specialized disciplinary expertise to strengthen the InTP processes.

Getting tactical

Since most of us operate in organizations that often have disparate functional elements of security, it’s important to figure out how to bridge the application of a more generalized framework with the practical needs of driving convergence across these security disciplines and domains. Let’s look at how we can take an ESRM framework and model it to work more effectively within a corporate environment.

For this, I again relied on the expertise of Josh Massey from MITRE to articulate some of the key considerations his team looks for when building and implementing a program. Josh and team have teased out a framework that is more relevant to the environment most of us are operating in. It also supports one of the key takeaways in Ontic’s Connected Corporate Security Report, which highlights the problems related to silos — including communication channels and decentralized data. Silos increase the likelihood that security decisions are being made without complete information.

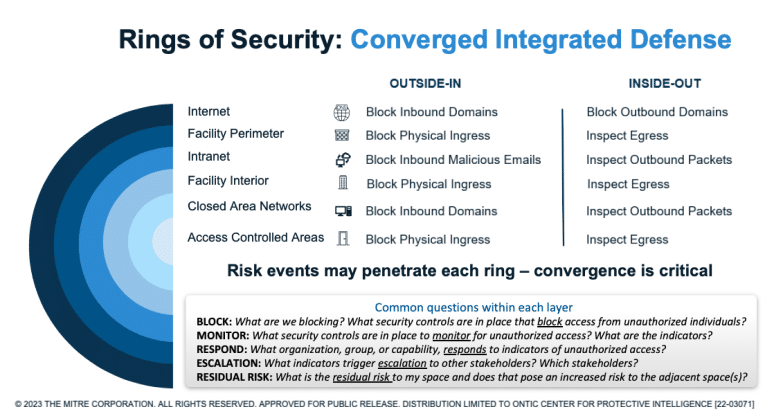

MITRE Converged Integrated Defense Framework

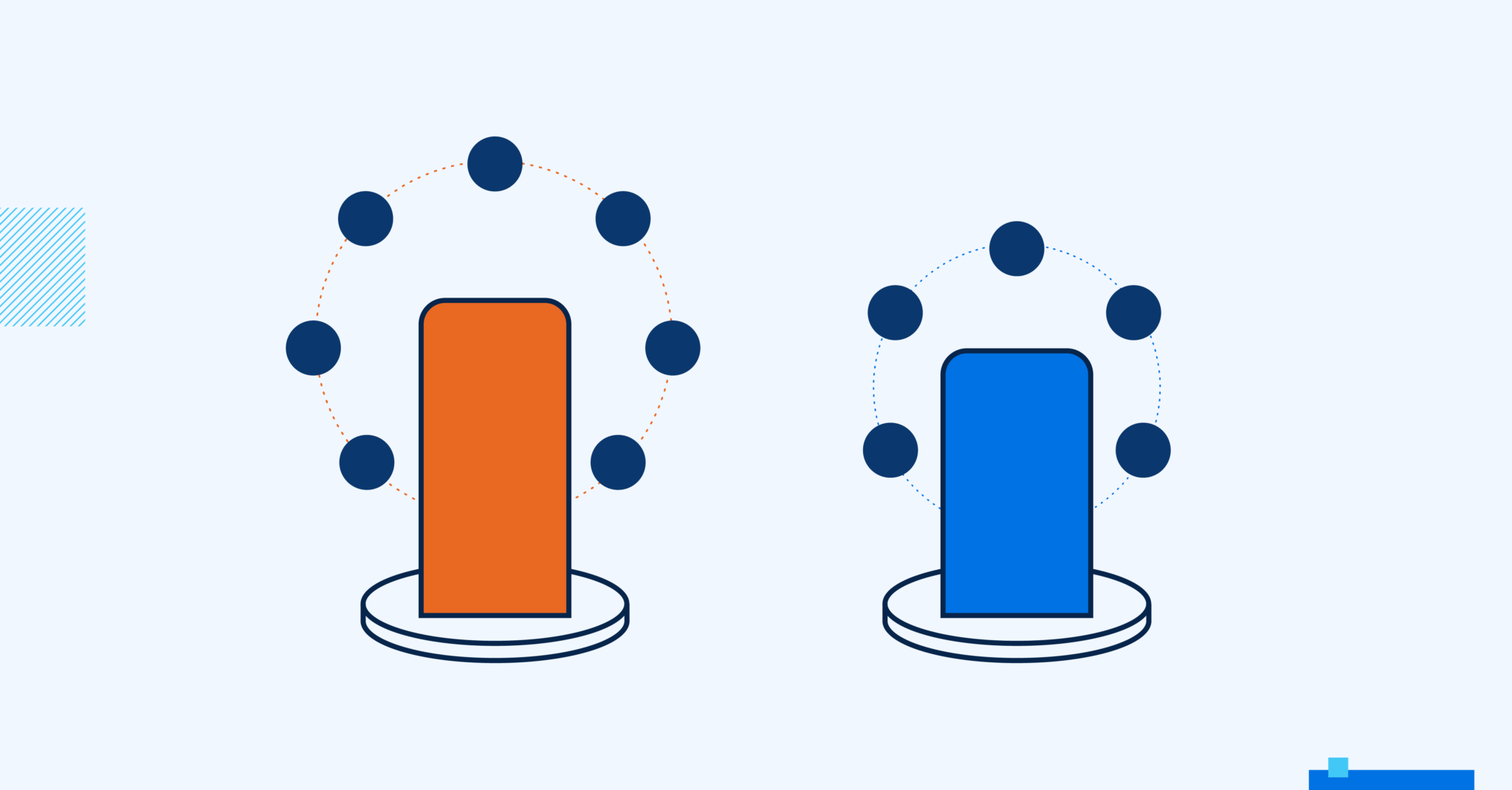

Principally, cybersecurity and traditional security domains can and should be viewed holistically as interdependent “rings of security.” When viewed in this converged manner, an organization is better postured with an integrated defense.

Many security domains understand the concept of “security in depth” within their domain but probably have never considered the value and impact of a converged, integrated defense that provides “security in depth” across multiple disciplines.

For the sake of this discussion, I will focus on the convergence of the physical and cyber domains. At a strategic level, a converged or integrated outlook would ensure overall a much higher level of security. While at a tactical level, it would enable tradeoffs in and at each domain as you become more aware of the supporting elements within the other domain. This more inclusive approach will inform where more robust protections are most needed.

For example, as you move “inward” to your most valued resources, tradeoffs become more impactful and should be considered with greater scrutiny. What is most interesting from viewing security in this matter is the realization that protections can operate across two spectrums: an “outside-in” view protects from external risk and “penetrations.” In contrast, an “inside-out” approach protects from trusted insiders and “exfiltration.” With this mindset, a much richer debate can occur over the value of any security control or mitigation.

So what do I mean by this “outside-in” or “inside-out” approach? Consider a converged or integrated defense as “rings of security” that provide “security in depth.” What makes it a converged or integrated model is that these rings do not represent one domain but multiple domains. In this example, the alternating cyber and physical “rings of security” from the outside-in would look like this:

Internet perimeter: Think of firewalls as your outermost “fence line,” which protects against unauthorized intruders from around the world.

Facility perimeter: Your fence line or facility boundary is the outermost physical security boundary and while still accessible by the public, any unauthorized intruder must be physically present at that location.

Intranet: This is the common network area accessible only by “trusted insiders,” but it is accessible by all trusted insiders.

Facility: Similarly, internal access to common facility areas is accessible only by “trusted insiders” but accessible by “all” trusted insiders.

Closed area networks: Information the organization deems sensitive or that warrants enhanced protection is controlled via closed area networks and is accessible only by a subset of your trusted insider population.

Access-controlled areas: Similarly, physical areas or resources the organization deems sensitive or warrant enhanced protection are protected via access-controlled areas accessible only by a subset of trusted insiders.

Each “ring of security” asks and answers the same fundamental questions but in accordance with different risk tolerances. A converged model also allows considerations of “tradeoffs” due to a more nuanced understanding of the security controls and mitigations across either adjacent ring.

The common considerations across each ring include the following:

- Block: What are you blocking? What security controls are in place that “block” access from unauthorized individuals? Just as important to understand, what are you still letting through, or what is the residual vulnerability to an adjacent ring?

- Monitor: What security controls are in place to monitor when unauthorized accesses are blocked and/or if a control is bypassed and an intruder can gain unauthorized access?

- Respond: What organization, group, or capability responds to unauthorized access at this ring? If multiple elements have a response responsibility, how do those elements communicate and share their alerts and response actions and findings?

- Escalation/collaboration: Who are the other stakeholders who may have the capabilities to support a response or should be notified of the primary response to be better informed of potential risks for their assigned space? Is there a platform or capability to document and track risks across spaces in a more unified manner?

- Residual vulnerability: What is the residual risk to my space, and does that pose an increased risk to the adjacent space(s)?

As mentioned in part one, security should not be viewed as a zero-sum game across/between security domains. We are not in competition with each other but instead are on the same team against a common adversary. The more we can begin to consider the resources and capabilities we each have in an integrated defense model, the quicker we can move towards a converged state where risks are understood and effectively mitigated against any threat that may emerge from outside or within our organizations.

This article was also written in partnership with Josh Massey, Director of Enterprise Risk of The MITRE Corporation’s Enterprise Security Assurance department. As such, Massey is responsible for establishing, executing, supervising, and directing the implementation and oversight of MITRE’s insider threat program and strategic protection initiatives across MITRE’s six federally funded research and development centers in the fields of defense & intelligence, aviation, civil agency modernization, homeland security, healthcare, and cybersecurity.