Executive Protection: The Fear of Kidnappings

- From a historical perspective, the perception of the kidnapping threat has driven the creation of many, if not most private executive protection teams.

- Threat of kidnappings is very low for high-net worth families and CEO’s in the United States.

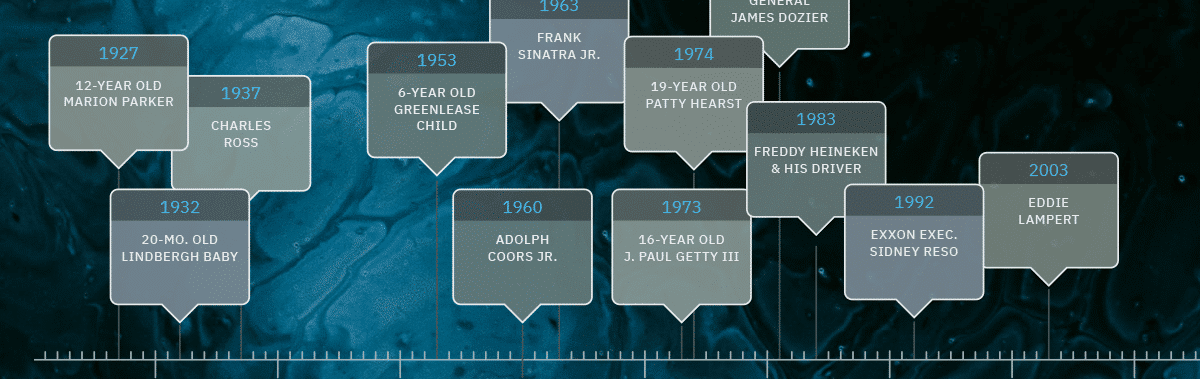

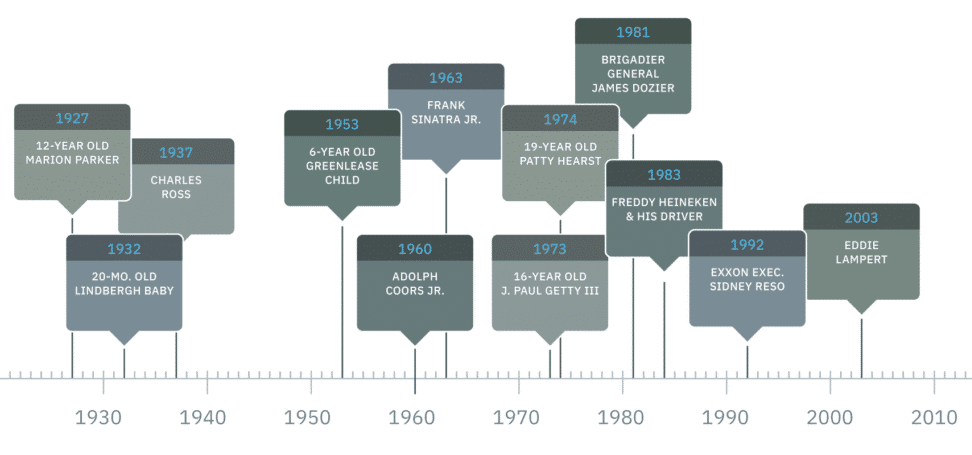

Notorious kidnapping cases helped shape the public perception of the need for protection for the rich and famous, for example, the kidnappings of the 20-month old Lindbergh baby (1932), Adolph Coors, Jr. (1960), Frank Sinatra, Jr. (1963), 16-year-old J. Paul Getty III (1973), 19-year-old Patty Hearst (1974), Brigadier General James Dozier (1981), Exxon executive Sidney Reso (1992), and hedge fund manager Eddie Lampert (2003.) Each one of these notorious cases also drove intense media attention with some ending in tragedy, e.g., the Lindbergh, Coors and Russo cases. Films like “The Bodyguard” starring Kevin Costner and Whitney Houston also shaped perceptions of the need for modern day bodyguards (1992.) Thwarted plans of kidnappings also are important to unpack and understand; for example, the plot to kidnap the 16-month old son of TV personality David Letterman from his Montana ranch (2005.)

In designing protection teams over the years and evaluating those in operation, I’ve also noticed a distinct psychological pattern with the client. In sum, every billionaire I’ve talked with regarding their personal security has expressed a fear that their children or significant other could be kidnapped. It’s one of the driving forces of their personal security decisions. Once I explained that the kidnapping threat is largely unrealistic inside the U.S. in the modern era and can be easily mitigated, there was usually a visible sigh of relief. I’ve come to believe that these kidnapping fears are not based on facts, but driven by perceptions and the media interest surrounding historical cases. As any parent knows, the threat of a child abduction is every parent’s worst nightmare, but it appears to be amplified inside the minds of the wealthy.

On a practical level, kidnapping is a high-risk business that can immediately bring to bear federal law enforcement resources, specifically the FBI. The 1960 abduction of the Coors heir is a perfect example of this, when J. Edgar Hoover recognized that it was a case that the G-Men needed to solve. Having done lots of hostage debriefings over the course of my career as a special agent, the “care and feeding” as we called it, of a captive is intense, resource driven, and time consuming. Rarely, do things work out well for the hostage.

In the continental United States, the kidnapping of children of high-net worth parents is extremely rare. And, in the modern era, I’m not aware of a single kidnapping that has occurred when the children of high-net worth parents have been afforded some degree of protective coverage for the family. It’s feasible that a kidnapping has occurred and not made public, but I doubt it; not in our social media world that we live in.

So, what are some practical solutions to mitigate the psychological fear of the kidnapping threat? I look at these steps: Baseline threat assessments; a good background check program on staff and insiders; an active protective intelligence program and platform, and routine counter-surveillance. Variants of these can be implemented for children at school, kids that are away at college, traveling family members, and for executives hunkered down due to the pandemic.

Visit Ontic’s Center for Protective Intelligence for strategies and best practices, insights on current and historical trends and lessons learned from physical security peers and industry experts.